Introduction

In this article I describe how one can set up a continuous integration / continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipeline using GitHub. This text is inspired by two sources. First one is “Nine simple steps for better-looking python code” by Vladimir Iglovikov. He gives the keys to better coding practices with CI/CD systems as its core. It is a great article and I wrote mine following the steps outlined there. So, “A practical guide for better-looking python code” is an accompanying/practical guide to Vladimir’s text. I advice you to go through the “Nine steps” for an overview of various approaches, although “A practical guide” could be read independently.

Second source is more subtle, and it is Joel Grus’ Ten Essays on Fizz Buzz where he describes ways to solve the Fizz Buzz coding exercise. While it provides the 10 solutions, it is more a discussion on Python, Maths, Testing and Coding. And if you don’t know Joel Grus, check out his presentation about his everlasting love towards Jupyter Notebooks.

Here are some resources that are associated with this article:

- GitHub repository where I performed my experiments. It is in a state after all the steps I describe below are implemented. However, you can see the development through git commits history.

- Along with setting up a CI/CD pipeline, it is possible to publish code documentation using GitHub pages. That’s what I did, and you can find the “documented” version of this article here. There are no changes to text, it is the same in the article and in the docs. I used Sphinx to create documentation.

I. Do not push to the master branch

The idea is that we want the master branch to contain the main code for our project. Even if we work on our own, it might be a good idea to always push to a different branch, and then integrate the code to the main branch through a pull request (PR). That way we can introduce various checks on pull requests, and impose structure on them. Let’s see how we can do it in GitHub.

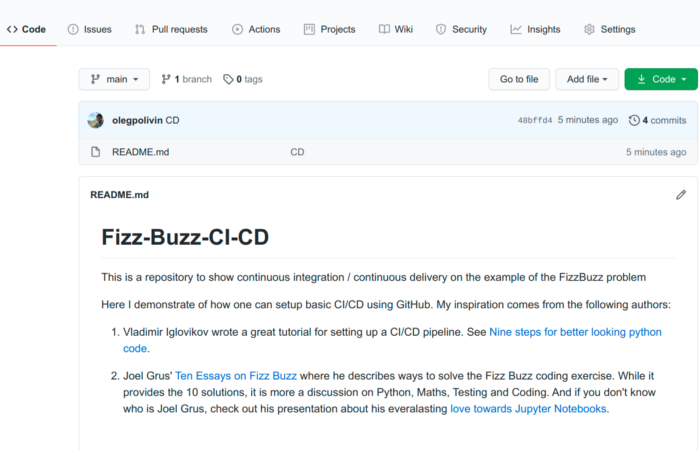

I create an empty repository to illustrate how one sets up a CI/CD pipeline step by step. So far it only contains a README.md file. It also has only one main branch, and nothing else. I clone it locally:

git clone https://github.com/olegpolivin/Fizz-Buzz-CI-CD.git

Starting point: an empty repo with a single README on main

Rules for branches

As usual I can work on the code, and then push to the main branch. That’s what I want to prohibit.

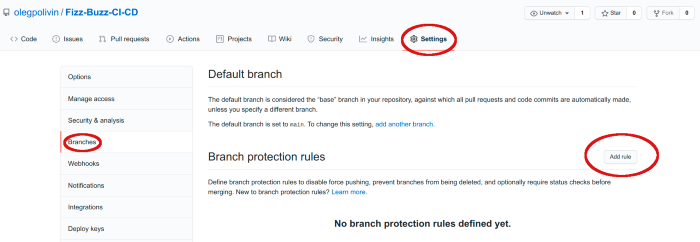

Go to the Settings menu for a given repo and choose Branches.

Navigate to Settings → Branches to configure protection rules

There are two ways to prevent pushing to the main branch, and you can choose it in the Add rule section. They are:

1) Require pull request reviews before merging. As it is written below:

when enabled, all commits must be made to a non-protected branch and submitted via a pull request with the required number of approving reviews and no changes requested before it can be merged into a branch that matches this rule.

However, indeed, this will prevent you from pushing to main branch, but you cannot be a reviewer of your own pull request as of November 2020. Therefore, if you are working on a project alone, this won’t let you merge PR into your main branch.

2) Setting up a CI/CD pipeline.

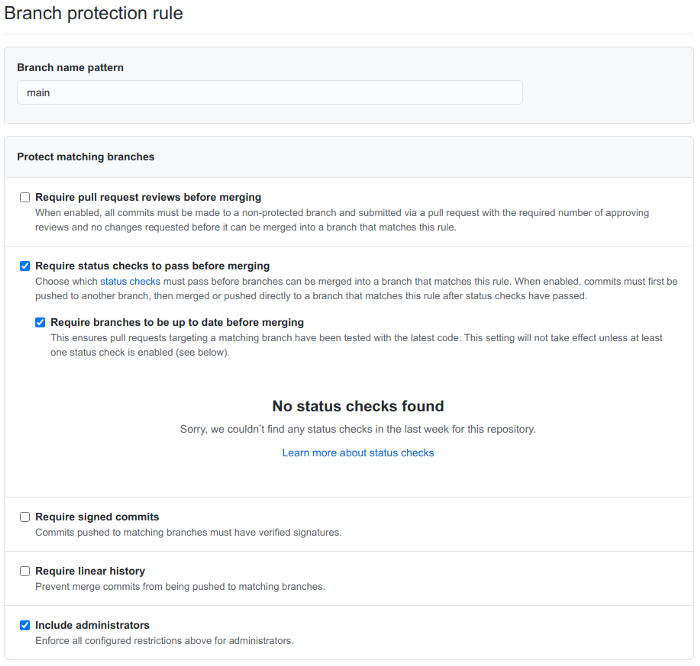

Click on Add rule, and here is the rule that I’ve added:

Add a protection rule for main with required status checks and admin inclusion

In particular, I have added:

- Require status checks to pass before merging (+ Require branches to be up to date before merging). So far there are no checks, but we will add them later.

- Include administrators: Even if we are alone on the project we don’t want to allow ourselves to push to main.

Let’s see how one can set up a CI/CD pipeline, so as to prevent pushing to the main. See the next section.

II. Continuous Integration / Continuous Delivery

In order to start with CI/CD using GitHub Actions one just needs to add a config file to the repository under .githib/workflows folder. You can find my configuration here.

Basic example

The most basic configuration file might be the following one:

# This workflow will install Python dependencies, run tests and

# lint with a variety of Python versions

# For more information see: https://bit.ly/3mX0m9V

name: CI

on:

push:

branches: [ main ]

pull_request:

branches: [ main ]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

matrix:

python-version: [3.7]

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v2

with:

python-version: ${{ matrix.python-version }}

- name: Cache pip

uses: actions/cache@v1

with:

path: ~/.cache/pip # This path is specific to Ubuntu

# Look to see if there is a cache hit for the corresponding requirements file

key: ${{ runner.os }}-pip-${{ hashFiles('requirements.txt') }}

restore-keys: |

${{ runner.os }}-pip-

${{ runner.os }}-

# You can test your matrix by printing the current Python version

- name: Display Python version

run: python -c "import sys; print(sys.version)"

It is not doing anything important. It makes use of GitHub Actions and the only thing it does is printing a python version, in my case “3.7”. Creating a pull request will run the script above. Pull request will always pass all checks, because the script checks nothing. However, the whole procedure prevents you now from pushing directly to main. Later we will add code formatters and a linter to this script.

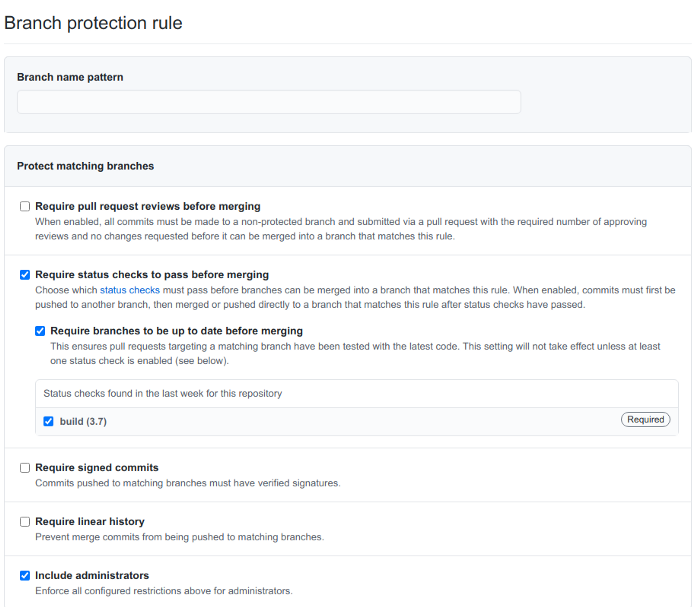

Set up a rule for your branch

It is necessary just to add some modifications to the Settings -> Branches -> Rules part. See what’s new:

Required check “build (3.7)” appears after configuring the workflow

Notice that build (3.7) has appeared among status checks. This corresponds to the name of the job (build) and python version 3.7. I made a small modification to the README.md file, and let’s see if I can push it now to the main branch. Here is the error I get:

Total 3 (delta 1), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (1/1), completed with 1 local object.

remote: error: GH006: Protected branch update failed for refs/heads/main.

remote: error: Required status check “build (3.7)” is expected.

To https://github.com/olegpolivin/FizzBuzz-CI-CD.git

! [remote rejected] main -> main (protected branch hook declined)

error: failed to push some refs to ‘https://github.com/olegpolivin/FizzBuzz-CI-CD.git'

Nice! The commit is rejected because a required status check is needed. Therefore, let’s push to a new branch. Locally, let’s create a new branch

git checkout -b dev

git push origin dev

A new branch called dev is created on the remote repository. What’s left is to create a pull request, and merge it to the main branch.

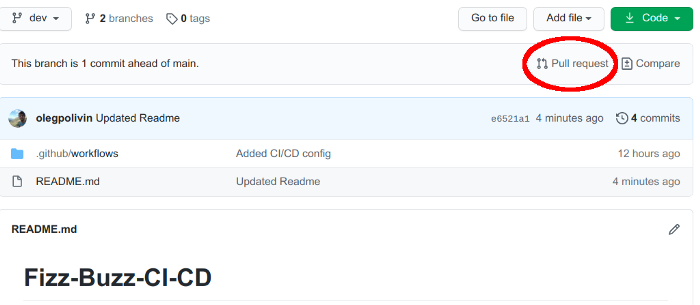

Create a PR from your feature branch to main to trigger checks

It becomes possible to merge after all checks are run:

All required checks pass—your PR is ready to merge

We would like to introduce actions or tests to be performed, before the pull request is ready to be approved, so let’s provide code that will be actually checked. We will consider solving the FizzBuzz problem, see the next section.

III. FizzBuzz

OK, it is time to write some code!

FizzBuzz Definition

Fizz Buzz problem is a task that sometimes people get during coding interviews. It goes like this (I take the definition from Joel’s book):

Print the numbers from 1 to 100, except that if the number is divisible by 3, instead print “fizz”; if the number is divisible by 5, instead print “buzz”; and if the number is divisible by 15, instead print “fizzbuzz”

Imagine we come up with a great code:

import scipy

import pandas

import numpy

import matplotlib

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

####### Here I start the solution to the fizz buzz problem #######

def fizz_buzz(n: int) -> str:

if n % 15 == 0: return 'fizzbuzz'

elif n % 5 == 0: return 'buzz'

elif n % 3 == 0: return 'fizz'

else: return str(n)

We were in a hurry, so we first imported everything that we usually import, made comments to visually show where the code starts, and printed if - return statements on the same line. Clearly, there is no newline at the end of file, who cares since the code is so great!

Actually, we do care because the code needs to be readable and beautiful, and we decide that it is a good idea to impose structure on every pull request. Also, code must pass linter checks and be formatted in a unified manner.

It is possible to add all the necessary checks that we want to impose in the ci.yml file that we created in the previous section. Let’s say we add:

- black formatter of the code

- isort to sort the imports in alphabetical order

- flake8 and pylint to inspect the code for conformity with good code practices

- MyPy as a static type checker

Extended GitHub Actions file

That’s how the ci.yml file looks like now:

# This workflow will install Python dependencies, run tests and

# lint with a variety of Python versions

# For more information see: https://bit.ly/3mX0m9V

name: CI

on:

push:

branches: [ main ]

pull_request:

branches: [ main ]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

matrix:

python-version: [3.7]

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v2

with:

python-version: ${{ matrix.python-version }}

- name: Cache pip

uses: actions/cache@v1

with:

path: ~/.cache/pip # This path is specific to Ubuntu

# Look to see if there is a cache hit for the corresponding requirements file

key: ${{ runner.os }}-pip-${{ hashFiles('requirements.txt') }}

restore-keys: |

${{ runner.os }}-pip-

${{ runner.os }}-

# You can test your matrix by printing the current Python version

- name: Display Python version

run: python -c "import sys; print(sys.version)"

- name: Install dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install black flake8 mypy pytest hypothesis isort pylint

- name: Run black

run:

black --check . --exclude docs/

- name: Run flake8

run: flake8 fizzbuzz.py

- name: Run pylint

run: pylint fizzbuzz.py

- name: Run Mypy

run: mypy fizzbuzz.py

- name: Run isort

run: isort --profile black fizzbuzz.py

Let’s now try to push the solution above to the repository.

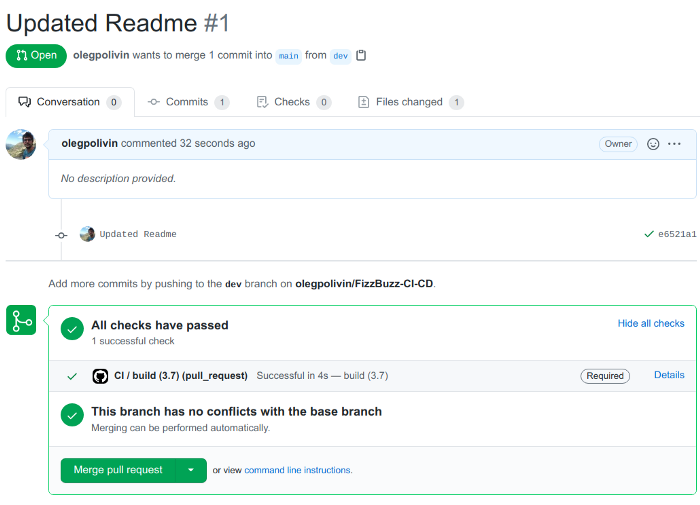

Example of a failing CI run—fix issues locally and push updates

And we see that it fails on the first check. When it fails it does not proceed to the next steps, but it turns out that the code above for solving the FizzBuzz problem will fail on every check.

A better version of fizzbuzz.py

The code below passes all of the checks that we have imposed on it.

"""Function to solve the fizzbuzz problem."""

def fizz_buzz(num: int) -> str:

"""This is my great and neat function to solve the famous

Fizz Buzz problem.

:param num: That's the number which we want the answer for

:return: fizz, buzz, fizzbuzz or the number itself

"""

if num % 15 == 0:

return "fizzbuzz"

if num % 5 == 0:

return "buzz"

if num % 3 == 0:

return "fizz"

return str(num)

Now when we push it to the dev branch, pull requests could be merged into the main branch since all checks are passed.

Catch the problem before committing

It might be that you want to learn that there are problems with your code (that is, it does not pass a check that one imposed) before committing. Yes, you will run the tests locally, but what if there is an additional point of control that does not allow you to commit your changes unless all the checks are passed? It is called a “Pre-commit hook”, and more on how to set it up in the next section.

IV. Pre-commit hook

A pre-commit hook is kind of a script that will be run when you do

git commit -m "<commit message>"

Link to the original and complete description of the pre-commit hook here.

Setting up the pre-commit hook

First install the pre-commit hook by running:

pip install pre-commit

It is necessary to create a .pre_commit-config.yaml file in the repository, where you would specify all the steps that should be done before the commit is performed. If an error is encountered, commit does not happen. Below is a simple .pre_commit-config.yaml configuration that

- Checks that code is formatted according to black.

- Sorts imports using isort.

- Uses flake8 and pylint as linters.

repos:

- repo: https://github.com/pre-commit/pre-commit-hooks

rev: v3.2.0

hooks:

- id: trailing-whitespace

- id: end-of-file-fixer

- id: check-added-large-files

- repo: https://github.com/pre-commit/mirrors-isort

rev: f0001b2 # Use the revision sha / tag you want to point at

hooks:

- id: isort

args: ["--profile", "black"]

- repo: https://github.com/psf/black

rev: 20.8b1

hooks:

- id: black

- repo: https://gitlab.com/pycqa/flake8

rev: 3.7.9

hooks:

- id: flake8

- repo: local

hooks:

- id: pylint

name: pylint

entry: pylint

language: system

types: [python]

After the file is created in the repository, run pre-commit install to install pre-commit into your git hooks. Et voilà, now the checks will run each time before the commit.

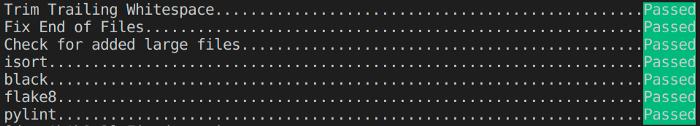

Testing the pre-commit hook

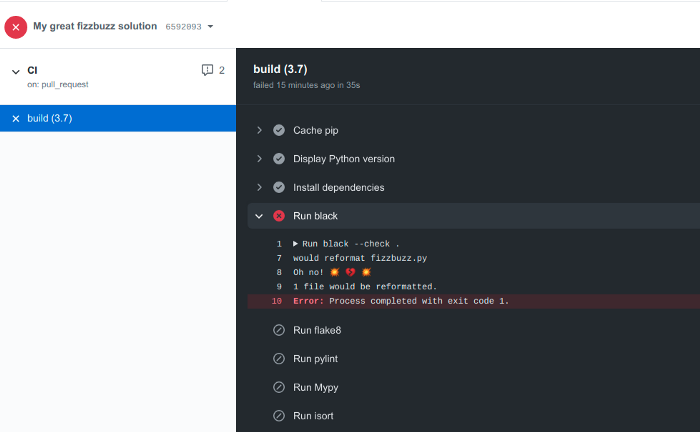

Here is a small test: let’s change the neat fizzbuzz.py code to get back to the one that does not pass the checks and see what happens. Here is a part of the result: we see where it fails. Note that the pre-commit hook modifies files for some commands (like black or isort).

Pre-commit prevents bad commits by running formatters and linters before commit

Coming back to the neat version of the fizzbuzz.py, the pre-commit hook test is passed. That’s how it looks like in my case:

All hooks pass—your changes are clean and consistent

Nice!

Finally, we want to not only check the formatting of our code, but also make sure that the code works correctly. We can add unit tests to the CI/CD pipeline!

V. Testing the code

In this section I show how to integrate unit tests into the CI/CD pipeline, and again we will make use of the ci.yml file. Personally, I like the pytest framework, and that’s what I will use in this section.

Setting up the test

There is only one function to test (fizz_buzz.py), and it is quite simple.

I will put the test_fizzbuzz.py function directly into the root folder. The structure of the current github project is as follows:

├── fizzbuzz.py

├── .github

│ └── workflows

│ └── ci.yml

├── .gitignore

├── .pre-commit-config.yaml

├── README.md

└── test_fizzbuzz.py

test_fizzbuzz.py contains:

"""Perform tests of the fizz_buzz function."""

import pytest

from fizzbuzz import fizz_buzz

inputs = [3, 5, 15, 4, 10, 115, 7]

outputs = ["fizz", "buzz", "fizzbuzz", "4", "buzz", "buzz", "7"]

@pytest.mark.parametrize("inp,out", zip(inputs, outputs))

def test_fizzbuzz(inp, out):

"""Takes inputs, gets the output of the fizz_buzz function.

Asserts whether equality holds.

"""

assert fizz_buzz(inp) == out

Append the code below to the ci.yml file:

- name: tests

run: pytest

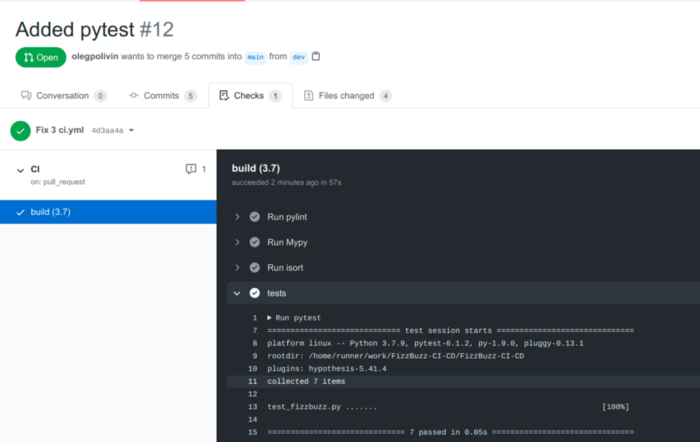

Passing the test

And here is the result:

Unit tests executed by pytest pass successfully in CI

But that was the case when everything is ok. We are happy.

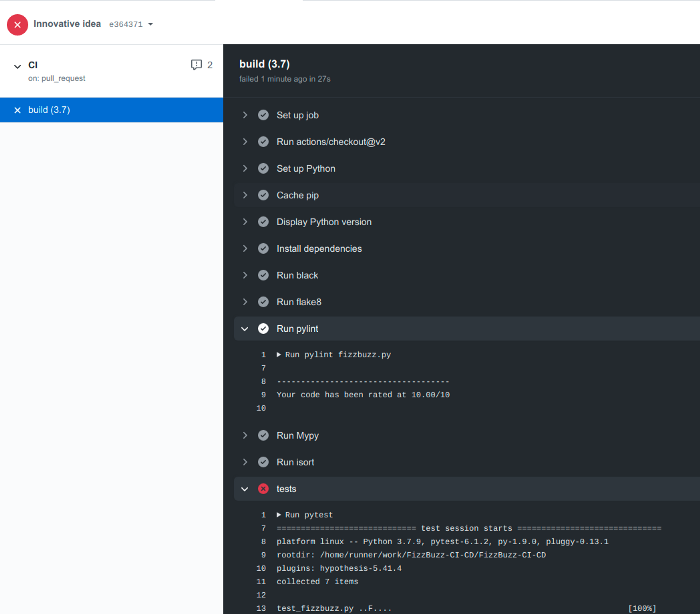

Failing the test

Now a new and innovative idea comes to our mind. Why overcomplicate the code, why do we start from “15”? Let’s “sort” the if-conditions in the code, the code will like so nice! So, we change the fizzbuzz code to the following one:

def fizz_buzz(num: int) -> str:

"""This is my great and neat function to solve the famous

Fizz Buzz problem.

:param num: That's the number which we want the answer for

:return: fizz, buzz, fizzbuzz or the number itself

"""

if num % 3 == 0:

return "fizz"

if num % 5 == 0:

return "buzz"

if num % 15 == 0:

return "fizzbuzz"

return str(num)

Great, let’s push and see that one test has failed:

Failing test demonstrates how CI guards against regressions before merge

That is, by introducing unit tests into the CI/CD pipeline we were able to catch the problem before merging pull request into the main branch.

Conclusions

That’s it for now. I hope you find this practice guide useful, and will apply it in your work. Try implementing just some of the steps or all of them: it feels great when you see it working in practice. I encourage you to read the “Nine simple steps for better-looking python code” for even more ideas on the subject.

I would be happy to get your comments and learn your ways to perform CI/CD and keep your code clean.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank

- Andrew Lukyanenko for helping me with details on CI/CD implementation.

- Vladimir Iglovikov for his article and his investment into openness and development of the whole Data Science community.

- I am grateful to the Open Data Science community (ods.ai) as a source of inspiration.

This article was originally publised on medium.